Design Diary 2. Mythic London

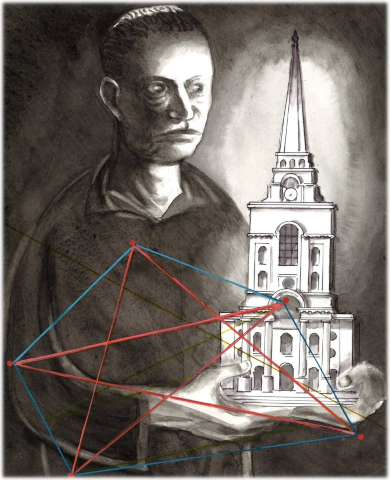

Illustration by Oscar Zárate

Part 2 of 8. Read part 1.

The District of Spittle-Fields draws heavily on London’s history and mythology. To find literary inspiration for a weird, otherworldly London, let us begin with the unholy trinity of Moorcock, Sinclair and Ackroyd.

Michael Moorcock is a Londoner; fantastic versions of the city turn up in many of his stories. Appendix N highlights his “Hawkmoon” Series (esp. the first three books), where the city of Londra is capital of the empire of Granbretan. And the London district of Notting Hill features prominently in the Jerry Cornelius tales.

To fully grasp Moorcock’s vision of mythological London, one must look beyond his genre fiction. Troynovante is a stand-in for London in his literary fantasy, Gloriana, or The Unfulfill’d Queen (1978). And his magnum opus Mother London (1988) can be said to have the city of London as its central character:

I drew from him my abiding interest in the mythology and legends of London… On walks he would speak of layered ruins like geological strata beneath our feet since unlike most old cities London bore few obvious signs of her antiquity… all her old rivers are turned into sewers and entire temples, churches, citadels lie below her modern concrete. Traditionally Boadicea is buried under Platform Ten at King's Cross Station, Bran's magical head lies below the Celtic burial grounds of Parliament Hill, Gog and Magog, the giants who ruled Lud's Town before 1200 BC when the Trojans conquered, still sleep near Guildhall and King Lud, who was once a god, might be found frozen within the foundations of St Pauls… Less exalted creatures like poor Annie Chapman, the Ripper's victim, continue to walk the meaner streets nearby.

The three protagonists in Mother London create a personal mythology to interpret the events in their lives, giving themselves a sense of meaning:

By means of our myths and legends we maintain a sense of what we are worth and who we are. Without them we should undoubtably go mad.

Moorcock also alludes to the ideas of the Multiverse developed in his Eternal Champion stories2:

Past and future both comprise London's present and this is one of the city's chief attractions. Theories of Time are mostly simplistic… but I believe Time to be like a faceted jewel with an infinity of planes and layers impossible to either map or to contain…

In his afterword to Lud Heat: A Book of the Dead Hamlets3, Moorcock praises the visionary genius of fellow Londoner Iain Sinclair, who:

… drags from London's amniotic silt the trove of centuries and presents it to us, still dripping, still stinking, still caked and frequently still defiantly kicking.

Lud Heat was published in 1975, based on a series of notebooks Sinclair kept while serving as a gardener for Tower Hamlets council. It is an experimental work, an eclectic collection of poetry and prose, presenting London as the mythic realm of King Lud and invoking the notion of psychic heat as an enigmatic energy contained in many of its places.

The book’s opening chapter, Nicholas Hawksmoor, his Churches, notes that on the old maps, the skyline was dominated by church towers. At the beginning of the 18th century, Hawksmoor was one of two Surveyors commissioned by Parliament to construct new churches. He built six — including Christ Church Spitalfields, the inspiration for the White Chappel in Return of the Ripper — and added obelisk-shaped spires to two others4.

Hawksmoor’s churches are curiously lacking in traditional Christian symbology, incorporating classical and pagan architectural elements instead. Lud Heat describes their architecture thus:

Certain features are in common: extravagant design, massive, almost slave-built, strength… It shocks every time you glimpse one of the towers. They are shunned. Their strength is hybrid, awkward: an admix of Egyptian & Greek source matter… Necropolis Culture… the Great Mausoleum at Halicarnassus re-enacted in Bloomsbury.

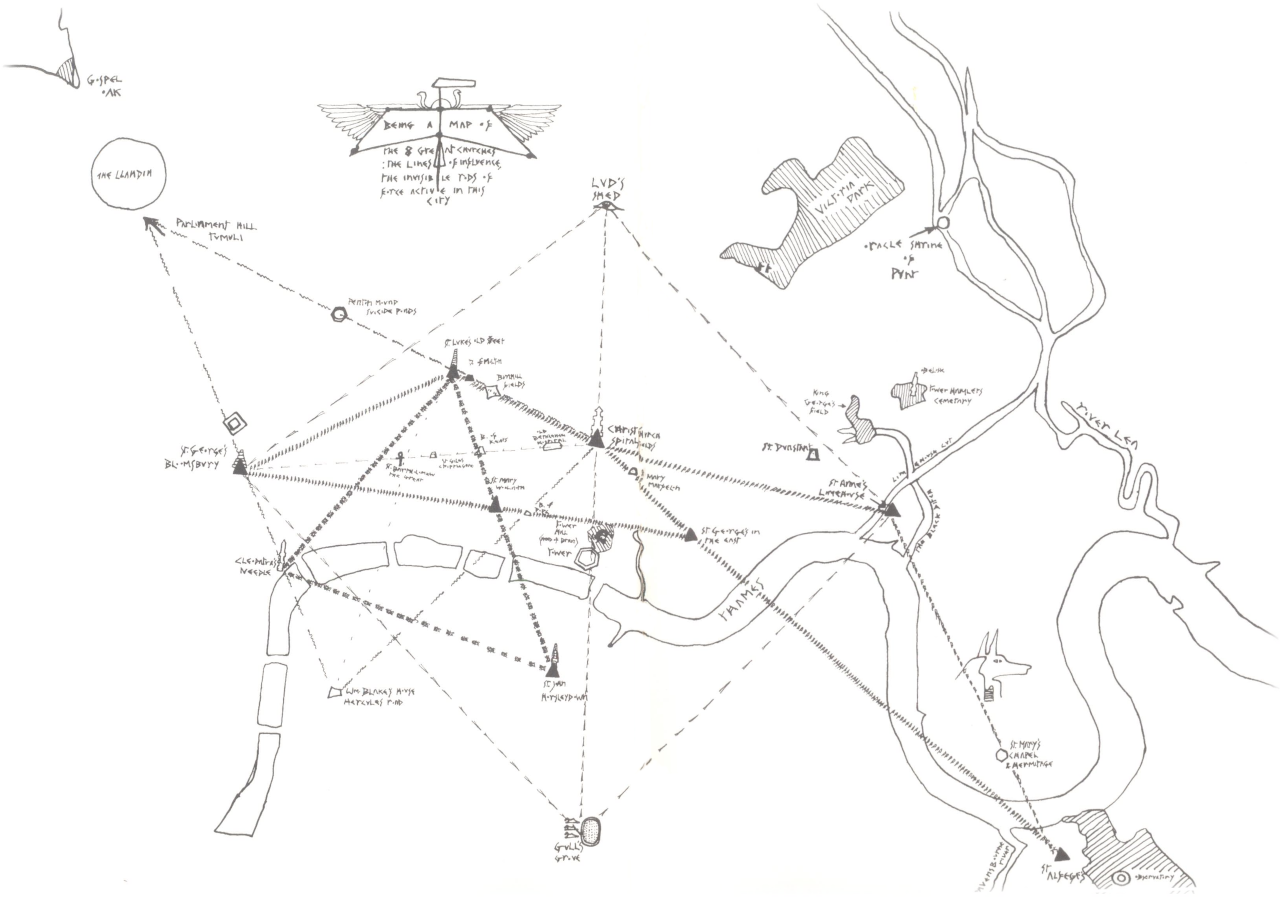

Sinclair presents a hand-drawn map showing sinister dotted lines linking the Hawksmoor churches, with pentacles and triangulations connecting the churches to plague pits and the sites of the Whitechapel murders and the Ratcliffe Highway murders from a century earlier. Thus he draws psychogeographic links between places in London and the events which happen there, a resonance between geography and history.

On the relationship between Christ Church Spitalfields and the Ripper murders, he says:

I spoke of the unacknowledged magnetism & control-power, built-in code-force, of these places: … the ritual slaying of Marie Jeanette Kelly in the ground floor room of Miller's Court, directly opposite Christ Church… The whole karmic programme of Whitechapel in 1888 moves around the fixed point of Christ Church, that Tower of the Winds — from the east in — closer & closer, until the risk of the final act is achieved…

Alan Moore’s From Hell and Moorcock’s Gloriana draw heavily on Sinclair’s psychogeographical vision. Another of Sinclair’s contemporaries was London’s biographer, Peter Ackroyd. In his gothic historical mystery, Hawksmoor (1985), Ackroyd credits “Iain Sinclair’s poem, Lud Heat, which first directed my attention to the stranger characteristics of the London churches”.

Like Moorcock, Ackroyd offers a non-linear view of time. Two parallel timelines centre around the same physical locations: the six historical churches designed by Hawksmoor, and a fictional seventh church. Parallel events in the 18th and 20th centuries create an effect of temporal simultaneity. In the 1710s, architect and occultist Nicholas Dyer builds the seven churches, for which he needs human sacrifices. In the 1980s, detective Nicholas Hawksmoor investigates murders committed in the same churches. Hawksmoor was the primary inspiration for the characters of Nicolas Hawkmoon and Mirabilis in Ripper.

Ackroyd’s prodigious output also includes non-fiction. London: The Biography (2000) chronicles London’s narrative arc from pre-history to the end of the 20th century. While broadly chronological, the book organises its chapters thematically. Rather than framing his narrative around the pivotal events of history, Ackroyd takes a microcosmic view, focussing on anecdotes and minutae. This book provided inspiration for the atmosphere and imagery of Spittle-Fields, including maps, plagues, crime and punishment and London’s rivers.

This post is an excerpt from Return of the Ripper Appendix N: Inspirational Sources.

Part 2 of 8. Part 3 coming soon.

Notes

1. Cover illustration for Nicholas Hawksmoor (c.1661–1736) by Owen Hopkins, published in The Architectural Review, April 2016 (paywall). Courtesy of Oscar Zárate/The Architectural Review.

2. In RPG circles, Moorcock is best known for his pulp fantasy books featuring Elric of Melniboné and the other aspects of the Eternal Champion. The publication of Mother London in 1988 recognised his ambition to be recognised as a literary writer, "As a writer of fantasy and satire he has achieved an international reputation. In recent years he has moved steadily away from this field and is now recognised as a major contemporary novelist." (quotation from the endpaper of Mother London). However, this was not the end of his fantasy works. The following year, he published another Elric novel, The Fortress of the Pearl (1989) and has continued to write Elric stories right up until today (the last at the time of writing being 2024's The Folk of the Forest).

3. Lud Heat was originally published by Albion Village Press in 1975. Michael Moorcock's afterword appears in the Skylight Press edition (2012).

4. See Nicholas Hawksmoor London Map by Owen Hopkins, Blue Crow Media, 2021. The obelisk spire of St. John, Horsleydown was destroyed in the Blitz, but the one on St. Lukes, Old Street can still be seen.